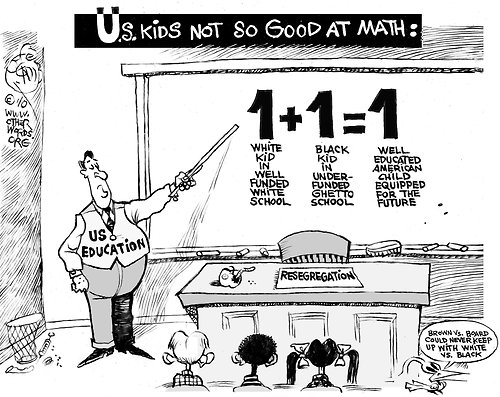

Desegregation in public schools proves to be a failure. Decades ago the Supreme Court ruled in Brown vs Board of Education “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” In sharing an integrated culture, we still live in a segregated climate.

Desegregation in public schools proves to be a failure. Decades ago the Supreme Court ruled in Brown vs Board of Education “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” In sharing an integrated culture, we still live in a segregated climate.

Segregated schools are defined as having 75 percent minority students – huffingtonpost.com.

HISTORY (After Brown vs Board of Education)

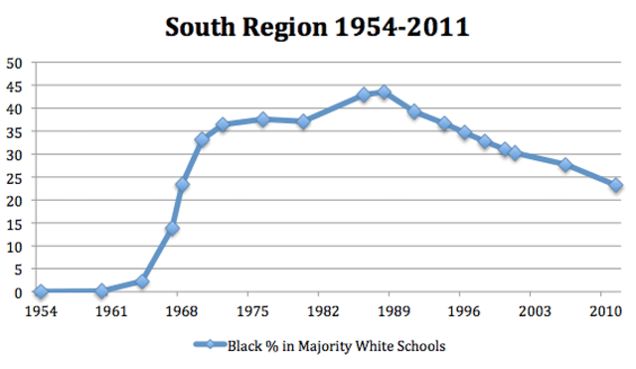

Southern states met the Supreme Court decision with much resistance. In 1956 Gov. Thomas Stanley – The Commission on Public Education – Virginia, requested that the General Assembly repeal compulsory education, close public schools, and provide vouchers to parents to enroll their children in segregated private schools. Thus, opening ‘segregation academies’ across the state of Virginia to block integration. This followed through the southern states. Shortly after, the federal government filed suit against segregated school districts and dismantled them.

By the ’70s, 90 percent of black students attended desegregated schools. Today, the gains are reversing. According to Slate.com, the average white student attends a school that is about 73 percent white, 8 percent black, 12 percent Latino, and 4 percent Asian-American.

Today’s Public Education System

Today’s Public Education System

Today there is a regional variation. Hyper-segregation is increasing across the board except in the former slave holding states that never joined the Confederacy. In the northeast, segregation in public schools moved from 43 percent in 1968 to 52 percent in 2011. Illinois is at 61 percent, Maryland at 53 percent and Michigan at 51 percent. These same schools have poverty rates larger than 90 percent. Meanwhile, impoverished schools with white and Asian clientele show only 2 percent poverty rates.

The Big Picture

In looking at the big picture, minority students in general have more exposure to each other and to whites than in the past.

A study from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, used data from the Department of Education to track the reading ability of first-graders. Findings indicated that black students in segregated school made smaller gains than black students in integrated schools. According to the Center for Civil Rights, segregation is still on the rise (eurekaalert.org).

Rising Problems

School segregation doesn’t simply happen – it begins with residential planning. Local neighborhoods can help to bring more integrated schools through low-income housing.

Students who walk or ride to school through impoverished neighborhoods and return to these neighborhoods after school are stressed and unable to focus on studies or homework assignments. How are they expected to achieve like children without these disadvantages?

Test scores may be the last culprit to the problem according to the Washington Post. A fixation on test scores and holding teachers accountable for the scores in schools having large numbers of disadvantaged students creates a desire to narrow the curricula through teaching time, effort, and resources robbing the non-tested areas for drill and kill in reading and math. There is no focus on problem solving strategies and building new knowledge. Some schools eliminate the arts and physical education to keep the focus on reading and math scores.

In USA Today, John Rury, education professor at the University of Kansas argues, “The reason for continued segregation is racial discrimination.” He also contends “the movement of more affluent families to school districts with better reputations and better resources play a role.”

The Center for American Progress found that public schools with at least 90 percent white students received an average of $733 more per pupil. Shouldn’t this be reversed?

Much data confirms the need for better school integration. For it to be successful, we must try to make it work. Giving up will not close the learning gap. Segregated schools with poorly performing students can rarely be turned around if students remain isolated. They are more likely to succeed if surrounded by peers with big dreams, parents who volunteer, and schools that have high expectations.